Comparisons of Relative Degrees of Jew-Hatred Throughout the Ages

Brit-Am Introduction by Yair Davidiy:

We trace the Lost Ten Tribes to Northern Europe. We use Ephraimite Criteria to determine which people descend from Israel and which do not. Any of our Criteria is relative degree of Jews Hatred. Germany is important. Very many inhabitants of the USA had ancestors who came from Germany. Israeltie Tribes who passed over to France and the British Isles sojourned in Germany. Germany fits some of the Ephraimite Criteria but does not measure up to the others.

We have reason to belive that the mass migrations from Germany to the USA in the 1700s and 1800s represented descendants of Israelites separating themselves from non-Israelite neighbors and moving to more Israelite surroundings. This is feasible. Contemporary records noticed differences in type between those who left and they who stayed behind. Their ideologies and attitudes as well as their relative degree of prejudice against Jews were also different. The same principles may also be applicable to other areas of Europe. We have some evidence for our understanding of this issue but we need more. The following article could help in this matter. It shows how within Germany historically different areas had varying degrees of hostility towards Jews. Some regions were much better than others. These variation persisted, as the study shows, for centuries. The article itself consisted of verbatim extracts from the quoted work of Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth. For relevant references as well as statistical graphs, etc, please go to the original article.

Source:

PERSECUTION PERPETUATED: THE MEDIEVAL ORIGINS OF ANTI-SEMITIC VIOLENCE IN NAZI GERMANY

Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth

Working Paper 17113

http://www.nber.org/papers/w17113

https://www.nber.org/papers/w17113.pdf

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

June 2011

Verbatim Extracts Only:

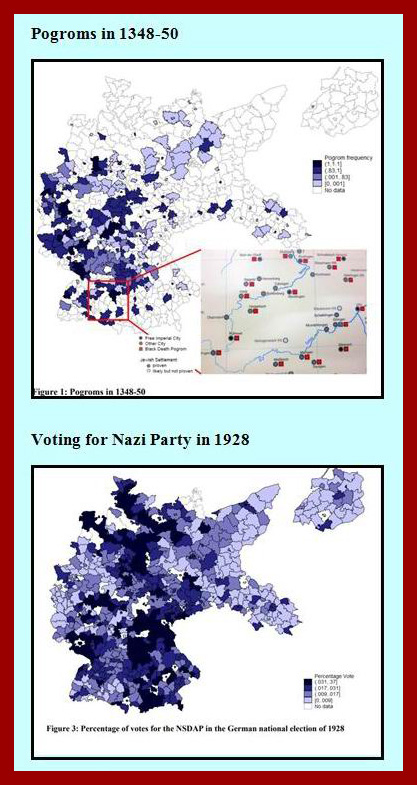

This paper uses data on anti-Semitism in Germany and finds continuity at the local level over more than half a millennium. When the Black Death hit Europe in 1348-50, killing between one third and one half of the population, its cause was unknown. Many contemporaries blamed the Jews. Cities all over Germany witnessed mass killings of their Jewish population. At the same time, numerous Jewish communities were spared. We use plague pogroms as an indicator for medieval anti-Semitism. Pogroms during the Black Death are a strong and robust predictor of violence against Jews in the 1920s, and of votes for the Nazi Party. In addition, cities that saw medieval anti-Semitic violence also had higher deportation rates for Jews after 1933, were more likely to see synagogues damaged or destroyed in the 'Night of Broken' Glass in 1938, and their inhabitants wrote more anti-Jewish letters to the editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Sturmer.

When the Black Death arrived in Europe in 1348-50, it was often blamed on Jews poisoning wells. Many towns and cities (but not all) murdered their Jewish populations. Almost six hundred years later, after defeat in World War I, Germany saw a country-wide rise in anti-Semitism. This led to a wave of persecution, even before the Nazi Party seized power in 1933. We demonstrate that localities with a medieval history of pogroms showed markedly higher levels of anti-Semitism inthe interwar period. Attacks on Jews were six times more likely in the 1920s in towns and cities where Jews had been burned in 1348-50; the Nazi Party's share of the vote in 1928, when it had a strong anti-Semitic focus, was 1.5 times higher than elsewhere.

Recently, the historical roots of present-day conditions have attracted attention. Fernandez and Fogli (2009) show that the fertility of immigrants' children continues to be influenced by the fertility in their parents' country of origin. Algan and Cahuc (2010) demonstrate that inherited trust is a powerful predictor of economic performance. Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2008) argue that free medieval cities in Italy still have higher levels of interpersonal trust today. There is also evidence that nationalities allowed to lend under Ottoman rule have higher bank penetration in the present (Grosjean 2011), that having been a member of the Habsburg Empire is associated with lower corruption in today's successor states (Becker et al. 2011), that the historic use of the plough in agriculture affects contemporaneous gender roles (Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn 2011), that the effect of changing religious norms on literacy can be permanent (Botticini and Eckstein 2007), and that the slave trade in Africa led to permanently lower levels of trust (Nunn and Wantchekon 2011). In a similar spirit to our paper, Jha (2008) argues that Indian trading ports with a history of peaceful cooperation between Hindus and Muslims saw less violent conflict during the period 1850-1950 and in 2002. We also connect with recent work looking at the long-run effects of 'deep' parameters such as technologicalstarting conditions, genetic origin, and population composition (Spolaore and Wacziarg 2009; Comin, Easterly, and Gong 2010; Putterman and Weil 2010).

Jews probably first settled in Germany during the Roman period.10 The documentary record begins around the year 1000, when there are confirmed settlements in major cities like Worms, Speyer, Cologne, and Mainz (Haverkamp 2002). By the 14th century, there were nearly 300 confirmed localities with Jewish communities. Pogroms against Jews began not long after the earliest confirmed settlements were established. The crusades in 1096, 1146, and 1309 witnessed mass killings of Jews in towns along the Rhine. In addition, there is a long history of sporadic, localized, and deadly attacks. The so-called Rintfleisch pogroms in Bavaria and Franconia in the late 13th century saw the destruction of many communities (Toch 2003). In the same category are the Guter Werner attacks (1287) in the mid-Rhine area, and the Armleder pogroms (1336) in Franconia and Saxony (Toch 2010). Many of the pogroms unconnected with the plague or the crusades began with accusations against Jews for ritual murder, poisoning of wells, or host desecration.

By far the most wide-spread and violent pogroms occurred at the time of the Black Death. One of the deadliest epidemics in history, it spread from the Crimea to Southern Italy, France, Switzerland, and into Central Europe. The plague killed between a third and half of Europe's population between 1348 and 1350 (McNeil 1975). Faced with a mass epidemic of unprecedented proportion in living memory, Christians were quick to blame Jews for poisoning wells and foodstuffs. After the first confessions were extracted under torture, the allegations spread from town to town.

The Jews of Zurich were relatively fortunate, they were merely expelled. Despite an intervention by the pope and declarations by the medical faculties in Montpellier and Paris that the allegations of well-poisoning were false, many towns murdered their Jewish populations.

Jews had been expelled from England in 1290 and from France in 1306/22. They were then partly recalled to France, and finally expelled in 1359. Outbreaks of anti-Semitic violence also occurred during the Spanish expulsion of 1492. In Basle, approximately 600 Jews were gathered in a wooden house, constructed for the purpose, on an island in the river Rhine. There they were burned (Gottfried 1985). Elsewhere, some city authorities and local princes tried to shield 'their' Jews; few were successful. The city council of Strasbourg intended to save its Jewish inhabitants. As a result, it was deposed. The next councilthen arrested the Jews, who were burned on St. Valentine's Day (Foa 2000). In some areas, peasants and unruly mobs set upon the Jews who had been expelled or tried to flee (Gottfried 1985). But in many cases, we can be certain that Jews lived in towns which did not carry out attacks. In Halberstadt in central Germany, for example, transactions with Jewish money lenders are recorded right before and during the Black Death; there is no record of any violence. The most likely interpretation, and the one we subscribe to, is that in locations where Jews lived, but where no pogrom occurred, anti-Semitic sentiment was weaker. This resulted in less pressure by artisans and peasants on the authorities to burn or expel the local Jewish community.

Another famous example of elites shielding Jews involves the Duke Albrecht of Austria. He initially intervened to stop the killing of Jews. Eventually, faced with direct challenges by local rulers to his authority, and under orders of his own judges, he had all the Jews living in his territories burned (Cohn 2007).

There is substantial uncertainty about the extent of elite involvement in the mass killings of Jews in general.

Towns in immediate proximity to each other, all with Jewish settlements, experienced a very different history of medieval anti-Semitic violence. While the Jews of Goppingen, for example, were attacked, those in Kirchheim escaped unharmed. The same contrast is visible for Reutlingen and Tubingen, or between Rottenburg and Horb. These towns are no more than 25 km apart. This is the level of variation at the local level which we will exploit in the quantitative analysis section of this paper.

In addition, Jews provided some of the leadership for the German revolution of 1918 and attempts to establish socialist regimes thereafter. In Munich, Kurt Eisner proclaimed a Soviet Republic; Gustav Landauer and Eugen Levine held positions of great influence. Rosa Luxemburg attempted to organize a revolution along Bolshevist lines.14 The ultra-left bid for power was eventually thwarted by demobilized army units. Radical right-wing groups quickly seized on the involvement of leading Jewish politicians in the revolution, the armistice, and the peace treaty of Versailles. The (incorrect) claim that Germany's army had been 'stabbed in the back' and not been defeated in battle pointed the finger at the revolution of 1918 as the key factor that lost the war.

Anti-Semitism was already widespread before the Nazi party's rise to power in 1933. Student associations would often exclude Jews. The desecration of Jewish cemeteries occurred with some frequency. Synagogues were besmirched with graffiti; politicians made anti-Semitic speeches (Walter 1999). In many hotels and restaurants, Jews were not welcome; elsewhere, entire towns declared themselves to be open for Christian guests only (Borut 2000).

According to the census of 1925, there were over 560,000 Jews living in Germany. The vast majority (66%) resided in the six biggest cities; the rest was evenly divided between smaller cities and over 1,000 towns and villages with a population size of less than 10,000.

During Weimar Germany's period of economic decline and social unrest after 1918, numerous right-wing parties with anti-Semitic programs sprang up. Hitler's National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP, aka the Nazi Party) was only one of many, but amongst the most radical. The German National People's Party (DNVP) continued the anti-Semitic rhetoric of the Imperial era (Hertzman 1963). Closest to the NSDAP was the German People's Freedom Party (DVFP), which split from the DNVP in 1922 because of the latter's lack of radical antiSemitism.

Mass deportations to the East began only in 1941. As early as 1938, Polish Jews living in Germany were rounded up and transported to the German-Polish border, and then forced to cross. Before that date, and during the pogroms of the 'Night of Broken Glass,' Jews from some towns were deported to camps in the Reich.

The city of Aachen provides a stark contrast with Wurzburg. Jews were first recorded in 1242, paying taxes. For the 13th century, several Jews born in Aachen are recorded in the lists of the dead of other towns. The town had a 'Judengasse' [street for Jews] in 1330. For Aachen, the Germania Judaica explicitly states that there is no record of anti-Semitic violence, neither before the Black Death nor during it. This is despite the fact that, in 1349, citizens of Brussels wrote to the Aachen authorities urging them 'to take care that the Jews don't poison the wells' (Avneri 1968). Aachen also saw no pogroms in the 1920s. The Sturmer published only 10 letters (or less than half the number for Wurzburg, despite a population that was 60% larger). Only 1% of voters in Aachen backed the NSDAP in 1928. 502 out of 1,345 Jews are known to have been deported, or 37% of the total. Next, we investigate how general these differences are.

The 1920s saw 33 pogroms in Weimar Germany overall. The frequency of attack was 8.4% in the 215 cities with pogroms in 1349, versus 1.5% in the remaining 1,030 cities without medieval Jewish settlements and/or Black Death pogroms. The fact that a town experienced a medieval pogrom thus raises the probability of witnessing another pogrom in the 1920s by a factor of approximately 6. The contrast is even more striking if we focus only on localities with confirmed medieval communities of Jews (panel B of Table 4): 19 pogroms were reported for the 294 cities, and out of these, 18 occurred in cities that also saw Black Death pogroms.

To illustrate the strength of our findings, consider the two towns of Konigheim and Wertheim. They are 10.3 km apart and had populations of 1,549 and 3,971 in 1933, respectively. Both had a Jewish settlement before the Black Death. Konigheim did not see a pogrom during the plague, but Wertheim did. The NSDAP received 1.6% of valid votes in Konigheim in 1928; in Wertheim, it received 8.1%.

Der Sturmer received 10-27% more letters, after controlling for population, from cities with Black Death pogroms. Both the size of a city (as expected) and of the Jewish population also go hand-in-hand with more Sturmer letters. The estimated impacts are sizeable. For example, a doubling of Jewish population is associated with 26-33% more Sturmer letters, similar to the result for medieval pogrom...

At the time of the Black Death, Jews were burned in towns and cities all over Germany, but not in all. In this paper, we demonstrate that the same places that saw violent attacks on Jews during the plague also showed more anti-Semitic attitudes over half a millennium later: They engaged in more anti-Semitic violence in the 1920s, were more likely to vote for the Nazi Party before 1930, had more citizens writing letters to an anti-Semitic newspaper, organized more deportations of Jews, and saw more attacks on synagogues during the 'Night of Broken Glass' in 1938. Strikingly, violent hatred of Jews persisted despite the fact that Jews disappeared in many towns and cities for centuries. Also, in contrast to many other findings in the literature on long-run effects of culture, the 'trait' we investigate yields no immediate economic benefit, on the contrary, the economic effect was likely negative because of the Jews' important role as traders and financial intermediaries. Nonetheless, anti-Semitic acts were often repeated in the same places more than half a millennium later.

Finding persistence over six centuries is in need of explanation. Low mobility is one likely factor, persistence disappears in faster-growing cities. In addition, we find partial support for Montesquieu's famous argument that trade encourages 'civility.' Hanseatic cities with a tradition of long-distance trade do not show persistence of anti-Semitism. In contrast, a history of political independence in general only weakens persistence.