"Tracing the Dispersion," ca. 1994

Terry M. Blodgett, Emeritus Professor of German, retired from Southern Utah University in 2010 after 37 years of teaching German language, German literature, linguistics, history of languages, and Hebrew. Education: Ph.D., U. of Utah.

Professor Blodgett has been a supporter of Brit-Am for some time. We do not necessary agree with every point made below but it is all pertinent to Brit-Am studies and of value.

This article has been slightly edited towards the end by Brit-Am.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Terry M. Blodgett, "Tracing the Dispersion," ca. 1994

What befell the Tribes of Israel's northern kingdom many centuries ago? That

question has been asked by students of the scriptures for generations. Like

any important historical topic, it is one that deserves careful and

thoughtful study.

Reconstructing ancient history, even religious history, can be compared to

putting together a large, complex puzzle with many of the pieces missing.

One must locate and assemble as many pieces as possible, then form as

accurate a picture of the past as the facts allow. In tracing Israel's

dispersion, therefore, many pieces may be considered: artifacts, vestiges of

ancient customs, archaeology, cultural anthropology, and scriptural and

historical accounts. This article explores only one such piece-that of

linguistic evidence.

Every Language Evolves

Language is a dynamic cultural phenomenon. It changes and grows. In our day,

modern technology, the sciences, and the media have accelerated the

acquisition of new words but, at the same time, have standardized spelling

and pronunciation. In the past, languages acquired new words more slowly,

but they were more likely to experience spelling and pronunciation changes.

Some of these changes took only decades; others took centuries.

One of the major sources of language change occurs when two groups of

people, each speaking a different language, come in contact with one

another. Each language influences the other, becoming a catalyst for change

and eventually settling into patterns characteristic of the languages

prompting the changes. These patterns serve as clues to help a linguist

determine what the language was like before the changes took place and which

languages caused the changes.

The basic conclusion of linguistic study into this subject is that as large

groups of ancient Israelites left their homeland-first, following the

Assyrian captivity of northern Israel (about 700 B.C.) and the Babylonian

captivity of Judah in the south (about 600 B.C.), and second, following the

Roman conquest of Palestine (about A.D. 70) - their language influenced the

languages of some of the countries to which they migrated. This linguistic

evidence can help us determine where some of these Israelites went and

approximately when. Although ancient Israelites were eventually scattered

throughout the entire world (see Amos 9:9), at least one general geographical area contains significant linguistic evidence to suggest that Israelite migrations did in fact occur there. That area is Europe.

Linguistic Evidence in Europe

From the Old Testament and other historical sources such as the annals of

the Assyrian kings, we learn that the northern kingdom, after years of war

and deportation, fell to Assyrian invaders in 721 B.C. Jeremiah emphasized

the north countries as being these Israelites' eventual destination.

See:

Jer. 3:12-18;

Jer. 16:14-16;

Jer. 23:7-8) and implied a western route (see Jer. 18:17; Hosea 12:1). Thus, a natural place

to look for what befell those remnants is to study the countries north and west of the Middle East.

It is of interest, therefore, to learn that in Europe, the centuries following 700 B.C. were marked by tremendous outside influence, and language

was profoundly affected. During the period between 700 and 400 B.C., numerous languages in Europe underwent major pronunciation changes and absorbed new vocabulary.2

This was particularly true of the Celtic languages, which were originally spoken

throughout Europe (700-300 B.C.) but gradually became more concentrated in

western Europe and Britain, and of the Germanic languages, which were spoken

in central and northern Europe and Scandinavia and eventually in England.

The gradual evolving of the sounds that make up words in a language,

particularly when two languages merge, is known by linguists as a sound

shift. The well-known pronunciation changes of the period of time between

700 and 400 B.C. have been called the Germanic Sound Shift, because they

were the most pronounced and systematic in the Germanic languages, which

include English, Dutch, German, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic. 3

Also during this same time period, the total vocabulary in the Germanic languages

increased by as much as one-third. 4 Linguists have long pondered what caused this sound shift and the increase in vocabulary. 5

One theory is that the technologically advanced peoples who introduced iron to

Europe (seventh century B.C. in Austria; sixth century B.C. in Sweden) also

influenced the language changes. Linguistic research supports this idea, as

well as the idea that these advanced peoples came from the Middle East,

where iron was in use. The research shows that the changes in language

resulted from an influx of Hebrew-speaking people into Europe, particularly

into the Germanic- and Celtic-speaking areas.

The Germanic Sound Shift

Most of the languages of Europe belong to the Indo-European family of

languages; that is, they are part of the linguistically linked group of

languages spoken in Europe and spreading as far east as Iran and India. For

many years, the peculiarities in the Germanic languages kept linguists from

recognizing that the Germanic languages belonged to the Indo-European group.

However, early in the nineteenth century, two linguists - Rasmus Rask from

Denmark (1818) and Jakob Grimm from Germany (1819-22) - showed that the

Germanic languages were indeed part of the Indo-European family but that

their differences in pronunciation were caused by a systematic shift in the

sound of two groups of consonants - [p, t, k] and [b, d, g]. 6 At the time of the sound shift, the pronunciation of these six consonants

was changed to [ph, th, kh] and [bh, dh, gh], respectively. These new sounds

were usually represented in writing by the letters f, th, h (x or ch) and b (v), d (th), g (gh). For example, by applying the rules of the sound shift

to the Indo-European "te puk" - replacing the t, p, and k with th, f, and x - we recognize the English words "the fox." Now the relationship between the

Indo-European word "pater" and the English word "father" becomes more recognizable.

Linguists generally agree that these changes began taking place sometime

after 700 B.C., and that the influence causing the sound shift continued to

affect the Germanic dialects for several centuries, at least until 400 B.C.

and possibly as late as the Christian Era.7

Unfortunately, scholars have not been able to agree upon what caused these

changes or where the original homeland of the peoples may have been.

Scholars have traced them to the Black Sea area, and to the Caucasus

Mountains, but research did not trace them beyond there, because the

scholars did not know whether that had been the people's first homeland or

they had come from the east or south of that point. My research took me to

the Middle East, and it was there that I found a likely cause for the sound

shift-the Hebrew language.

The first thing I noticed was that Hebrew shifted the same six consonants

that were shifted in Germanic-[p, t, k] and [b, d, g]. In ancient Hebrew,

these consonants carried a dual pronunciation. Often, they did not shift,

but when they began a syllable that was preceded by a long vowel, or ended a

syllable, then [p, t, k] and [b, d, g] shifted to the sounds [ph, th, kh]

and [bh, dh, gh]. Thus, the Hebrew word for "Spain," 'separad,' was pronounced

'sepharadh,' and the word for "sign," spelled 'ot,' was pronounced 'oth.'

In 700 B.C., this sound shift was still functional in Hebrew and would have

been part of any impact that migrating Israelites would have had on other

languages. The fact that the same consonants were involved in similar sound

shifts in both Hebrew and Germanic dialects at about the same time is

significant. Yet even more significant is that the sounds [ph, th, kh] and

[bh, dh, gh], so prevalent in Hebrew, did not exist in Germanic before the

sound shift occurred. 8

A Comparison of Hebrew and Germanic

The case for a Hebrew influence on Germanic is further strengthened by a

close comparison of the two languages, and particularly of the changes that

developed in Germanic following the Assyrian captivity of Israel. The

changes fall generally into three categories: pronunciation, grammar, and

vocabulary.

In addition to the similar sound shifts just described, there were other sounds common to both Hebrew and Germanic that did not

generally appear in the Indo-European languages. For example, when Hebrew

and Germanic consonants appeared between vowels, they normally doubled if

the preceding vowel was short. This doubling of consonants, referred to as

gemination, became a characteristic feature of Germanic but not of other

Indo-European languages. In this way, Indo-European media became Old English

middel and modern English middle.

Almost half of the Hebrew verb conjugations required doubling the consonant

and substituting a shortened vowel preceding the consonant. Compare Hebrew

shabar ("to break") and the related Hebrew form shibber ("to shatter").

Likewise, almost half of the Germanic verbs doubled the middle consonant and

substituted a shortened preceding vowel: Indo-European sad- and bad- became

settan ("set") and biddan ("bid") in Old English. 9

2. Grammar. At the time of the Germanic Sound Shift, the Germanic dialects

experienced a sharp reduction in their number of grammatical cases, making

Germanic more like Hebrew. As in English, the case (or form) of a noun,

pronoun, or adjective in a Germanic language indicated its grammatical

relation to other words in a sentence. At the time of the Germanic Sound

Shift, the Germanic dialects immediately reduced the number of possible

cases for a word from eight to four (as in modern German) and eventually to

three (as in English, Spanish, and French). These were the same three cases

(with possible remnants of a fourth) that Hebrew used before the Assyrian

and Babylonian captivities -nominative case (indicating a word is the subject

of a sentence), accusative case (indicating a word is the object of a verb

or preposition), and genitive case (used to indicate a word in the

possessive form). 10

Indo-European had six verb tenses. Hebrew, on the other hand, contained only

two tenses (or aspects), dealing with actions either completed or not

completed. Germanic, likewise, reduced its number of tenses to two-past and

present. The other tenses in modern Germanic languages have developed out of

combinations of these two original tenses.

Verb forms in the two language groups also contain similarities. The Hebrew

verb kom, kam, kum, yikom ("to arise, come forth"), for example, compares

favorably with modern English come and came, Old English 'cuman,' and German

'kommen,' 'kam,' 'gekommen' ("to come forth, arrive, arise").' 11

3. Vocabulary. Perhaps the most convincing similarity between Hebrew and

Germanic lies in their shared vocabularies. Linguists recognize that about

one-third of all Germanic vocabulary is not Indo-European in origin.12

These words can be traced back to the Proto-Germanic period of 700-100 B.C., but

not beyond. Significantly, these are the words that compare favorably in

both form and meaning with Hebrew vocabulary. Once a formula was developed

for comparing Germanic and Hebrew vocabulary, the number of similar words

identifiable in both languages quickly reached into the thousands.

According to this formula, words brought into Germanic after 700 B.C. had a

tendency to modify their spelling in three ways:

First, in most Germanic dialects, the words changed in spelling according to

the sound shift. Hebrew, on the other hand, changed only in pronunciation;

spelling remained the same. For example, Hebrew 'parah' ("to bear oneself

along swiftly, travel") remained parah when written, but was pronounced

[fara] if it was preceded by a closely associated long vowel. With that in

mind, it is easy to recognize the same word in Old Norse and Old Frisian (a

dialect in the Netherlands): 'fara' ("to travel, move swiftly").

[Editorial Note: Regarding the above-mentioned verb "parah" we do not know what explicit Hebrerw word the author is here referring to.]

Second, the vowels in the initial syllables were frequently dropped in

written Germanic forms because Hebrew words usually carried the accent on

the last syllable. Compare Hebrew 'daraq' and English 'drag.' Occasionally, if

the initial consonant was weak, the entire syllable dropped out, as in

Hebrew 'yelad' ("male offspring, son") and English 'lad,' and in Hebrew 'yi-fal'

("to fall") and English 'fall.'

Third, Hebrew used a tonal accent (a vocal emphasis featuring a tone or

sound in part of a word) rather than a stress accent (a vocal emphasis

featuring increased volume in speaking part of a word), but this changed to

a stress accent in the Germanic dialects. However, the effects of the Hebrew

tonal accent are evident in Germanic. The Hebrew tone, which usually

appeared in the final syllable, was often represented in written Germanic by

one of four tonal letters - l, m, n, or r. Compare Hebrew 'satat' ("to place,

found, base, begin") with English start (r represents the Hebrew tone), and

Hebrew 'parak' ("to be free, to liberate") with English 'frank' ("free; free

speech" - in which p was shifted to f, the unaccented 'a' [in "parak"] was deleted, and 'n' was

added for the Hebrew tone).

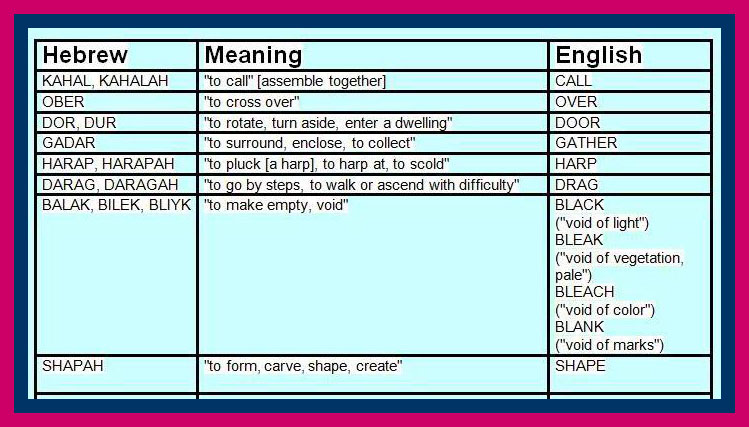

Similarities in Hebrew and English words point to their common roots.

Some Hebrew-English Cognates

New Germanic Words from Hebrew Word Roots

Biblical Hebrew contained relatively few root words-originally only a few

hundred-but from these roots, words were formed in great variety. Most of

these formations were made by exchanging vowels, adding prefixes or

suffixes, and doubling consonants according to certain rules. Literally

thousands of words similar to these roots, and to the multiple forms that

developed out of these roots, appeared in Germanic dialects between 700 and

400 B.C. One example is the Hebrew word 'dun' or 'don'. The root is 'dwn' and is

related to the root 'adan' ("to rule, to judge, to descend, to be low, area

ruled or judged, area of domain"). The proper name 'Dan' ("judge") is related

to this root. Out of this root also developed the Hebrew word 'adon' ("Lord,

Master"). These words remind us of the Anglo-Saxon word 'adun,' out of which

the English word 'down' (the noun form means "hill, upland") developed and the

area ruled was 'don,' or its modern counterpart town. It is also interesting

to note that the Hebrew word 'adon' ("Lord") and its root 'adan ("to rule,

judge") compare well with 'Odin' and 'Wodan,' two names from different dialects

for the highest Germanic god.

The High German Sound Shift

The influence of Hebrew on the Germanic languages does not end with the

Germanic Sound Shift of 700-400 B.C. About a thousand years after the first

sound shift, the Germanic dialects in northern Italy, Switzerland, Austria,

and southern Germany began a second phonetic change involving the same six

consonants.13 Beginning in the south about A.D. 450, this second sound shift,

referred to as the High German Sound Shift (since it originated in the

highlands of the Alps), spread northward into Switzerland and Austria. By

A.D. 750, it had spread to the dialects of southern Germany. This High

German dialect continued to grow in popularity (in the sixteenth century

Martin Luther used it in his translation of the Bible) until it eventually

became the standard form of German.

The major difference between the Germanic Sound Shift of 700-400 B.C. and

the High German Sound Shift of A.D. 450-750 was that [t], which shifted to [th] in the first sound shift, shifted consistently to

[s] in the second one. This caused the word 'water,' for example, to be

pronounced 'wasser,' and 'white' to be pronounced 'weiss.' This shift of [t] to

[s] is an important clue to the source of influence for this second sound

shift in southern Germanic territory. It leads us, once again, to the Middle

East-but this time to the Aramaic language.

The Aramaic Influence

When Persia conquered Babylon, Cyrus the Great freed the captive Jews and

allowed them to return to their homeland in Palestine. However, not all

wanted to leave the beautiful city of Babylon to return to their country,

which had been destroyed. Some stayed. Many from the tribes of both Judah

and Benjamin returned. Those who returned to Palestine found themselves

surrounded by Aramaic-speaking peoples, and they soon adopted Aramaic as

their everyday language. 14

As a consequence, the Jews were speaking Aramaic in A.D. 70 when the Romans

overran Jerusalem and sent thousands of Jews fleeing Palestine. During the

following years, many of these Aramaic-speaking Jews made their way

northward into Europe. The Christianized Jews, especially, sought the refuge

of the Italian Alps, and by A.D. 450, they had established a sizable

population there. During the following centuries they gradually spread

northward into Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. 15 Historians have documented these migrations well, but they have failed to

recognize the influence of these people's language on the languages they

encountered. Aramaic had originally employed a sound shift identical to the

Hebrew sound shift, but by 500 B.C. when the Jews learned it, the language

had made a small but significant change in its pronunciation. Aramaic began

shifting [t] to [s] rather than to [th], as both Hebrew and Aramaic had done

previously. 16

This is also the characteristic difference between the first Germanic Sound

Shift of 700-400 B.C. and the High German Sound Shift of A.D. 450-750. 17 For example, in comparing the Hebrew/Aramaic changes with the first and second

sound shifts, we note that the Jews at the time of their dispersion

pronounced, for example, the Hebrew words bayit ("house") as 'bayi's and 'gerit'

(from gerah "roughage, grits") as 'garis. 'By comparison, the German word for

grit ('griot,' "groats") made a similar change to 'grioz,' then to 'griess,'

during the High German Sound Shift. These changes suggest the influence of

Aramaic in the southern Germanic dialects. Additional Hebrew vocabulary was

added to the southern German, Austrian, and Swiss dialects during this later

period (compare Hebrew 'pered,' "beast of burden," with German 'Pferd,'

"horse").

Two Hebraic Sound Shifts

Thus, what have come to be known as the Germanic Sound Shift and the High

German Sound Shift appear to have been a Hebraic sound shift and a closely

related Aramaic sound shift that influenced the Germanic dialects at two

separate periods of history. Research also shows that the linguistic mark of

the sound shifts, supported by other linguistic similarities, particularly

the vocabulary, can be used as a means of tracing Israelite groups

throughout the world. So far, the evidence seems to point to Europe as a

major destination, particularly to the Germanic- and Celtic-speaking

countries of Scandinavia, Britain and the European mainland.

The Gathering of Israel

The role that Abraham's descendants would play in the course of world

history was foreshadowed early in the biblical record. To Abraham the LORD

said, "I will make thee exceeding fruitful, and I will make nations of thee,

and kings shall come out of thee." Gen. 17:6.)

The LORD renewed this promise with Isaac (see

Gen. 26:4) and again with Jacob, saying that his descendants would "spread abroad to the west, and to the

east, and to the north, and to the south: and in thee and in thy seed shall

all the families of the earth be blessed." (Gen. 28:14).

This spreading would come as Moses foretold: Israel would someday be

scattered "among the nations, and ... be left few in number among the

heathen, whither the Lord shall lead [them]." (Deut. 4:27.) This would be a

thorough dispersion. As the LORD said in Amos 9:9, he would "sift the house of

Israel among all nations." But he also promised that he would not forget

Israel. Eventually, the children of Israel would be gathered "out of the

lands, from the east, and from the west, from the north, and from the

south." Ps. 107:3.)

Although Israel would be scattered throughout the world, the countries north

of Israel were particularly singled out as lands from which Israel would be

gathered. Jeremiah wrote that "the days come, saith the LORD, that it shall

no more be said, The LORD liveth, that brought up the children of Israel out

of the land of Egypt;

"But, The LORD liveth, that brought up the children of Israel from the land

of the north, and from all the lands whither he had driven them." (Jer. 16:14-15).

Changes in language provide only one kind of linguistic evidence we can use

to identify the dispersion of Israel. Other linguistic evidence can be found

in place names and in the names of various ancient peoples who lived north

of the Middle East following the captivity of Israel. Many of these people

migrated farther north and west into Russia, Scandinavia, Europe, and

Britain.

The apocryphal book of 4 Ezra (a continuation of the book of Ezra in the Old

Testament) describes how Shalmaneser, King of Assyria, took northern Israel

captive. It also indicates, as Isaiah prophesied (see

Isa. 10:27), that at least some of the Israelites escaped their captors and fled north.

According to the account in 4 Ezra (referred to in some editions as 2 Esdras), the fleeing captives "entered into Euphrates by the narrow passages

of the river" and traveled a year and a half through a region called

"Arsareth." (4 Ezra 13:43-45.)

The narrow passage could refer to the Dariel Pass, also called the Caucasian

Pass, which begins near the headwaters of the Euphrates River and leads

north through the Caucasus Mountains. At the turn of the century, Russian

archaeologist Daniel Chwolson noted that a stone mountain ridge running

alongside this narrow passage bears the inscription 'Wrate Israila,' which he

interpreted to mean "The Gates of Israel." 18 These narrow passages lead through a region called 'Ararat' in Hebrew, and

'Urartu' in Assyrian. Chwolson writes that Arsareth, mentioned in 4 Ezra, was

another name for Ararat, a region extending to the northern shores of the Black Sea 19

A river at the northwest corner of the Black Sea was anciently named 'Sereth'l (now

Siret), possibly preserving part of the name Arsareth. Since 'ar' in Hebrew

meant "city," it is probable that Arsareth was a city - the city of

Sareth-located near the Sereth River northwest of the Black Sea.

A number of other geographical locations in the area of the Black Sea have

names that suggest Hebraic origins. For example, the names of the four major

rivers that empty into the Black Sea seem to have linguistic ties to the

tribal name of Dan. They are the Don (and its tributary the Don-jets), the

Dan-jester (now Dnestr), the Danube (or Donau), and the Dan-jeper (now

Dnieper). North of the Caspian Sea is a city called Samara (Samaria). There

is also a city of Ismail (Ishmael) on the Danube, and a little farther

upstream is a city called Isak (Isaac).

Chwolson and others of the Russian Archaeological Society found more than

seven hundred Hebraic inscriptions in the area north of the Black Sea.

According to Chwolson, one of these inscriptions refers to the Black Sea as

the "Sea of Israel." On the Crimean Peninsula was a place referred to as the "Valley of Jehoshaphat," a

Hebrew name, and another place was called "Israel's Fortress." 20 According to the Russian archaeologist Vsevolod Mueller, there was an

"Israelitish" synagogue at Kerch (a city on the Crimea) long before the Christian era. 22

It is difficult to date these inscriptions, but some of them contain

information relating to the fall and captivity of Israel. Others appear to

have been written about the time of Christ and even later, indicating that

the area north of the Black Sea contained an Israelite population for many

centuries. One of these inscriptions mentions three of the tribes of Israel

as well as Tiglath-pileser, the first Assyrian king to transport large

segments of the population of Israel to Assyria.

[Brit-am Editor's Note: It has since been proven that a portion (but not necessarily all) of these inscriptions were forged by the Karaiate scholar Abraham Firkovitch (1786-1874). "Chwolson alone defended him, but he also was forced to admit that in some cases Firkovich had resorted to forgery." He wished to present his own Karaite community as descended from the Ten Tribes and residents of the area before the death of the Christian Messiah. The Karaiates according to this would therefore not be culpable, as the Jews were claimed to be, for his death. Firkovitch was succesful in this in so far as the Russian authorities did not persecute the Karaites to the same degree as they did the Jews.]

The Russian archaeologists also found mounds, or heaps of earth, dotting the

landscape. These mounds, stretching across the entire region north of the Black Sea where the

Hebraic inscriptions were found, turned out to be elaborate burial chambers,

often containing a leader of the people with some of his possessions.

Although mound building was not a typical type of burial in the Middle East,

"high heaps" or "great heaps" are described as a means of burial in several

Old Testament passages. (See Josh.7:26, Josh. 8:29; 2 Sam. 18:17.) Furthermore, the

people of Ephraim were commanded in the Old Testament specifically to build

up "high heaps" as "waymarks" as they traveled. (See Jer. 31:21.)

The mounds stretch from the Black Sea northward through Russia to the top of the Scandinavian

Peninsula, then southward to southern Sweden - where thousands of mounds are

found. Similar burial mounds are also found in Britain and western Europe, indicating other

migrations in westerly and northwesterly directions.

Herodotus (6:126) identified the first of the mound builders in the Black Sea area

as Kimmerioi; The Romans referred to them as Cimmerii, from which we have the name Cimmerians.

They called themselves Khumri, which refers to "the Dynasty of King Omri."

Omri was king of northern Israel about 900 B.C. He founded Samaria and

established the capital of Israel there. His mode of government made him

popular throughout the Middle East, and northern Israel came to be known by

his name, politically, from that time on.

There are other peoples throughout Europe and Asia whose origins trace from

this area and whose names seem to have a Hebrew root. Among these are the

Galadi (the root word probably comes from the biblical Gilead, the region

east of the Jordan River, pronounced Galaad in that region and in Assyria

and the Celts (a Germanic pronunciation of Galadi); the Gallii (or Gali,

root word probably from the biblical Galilee), also called Gals, Gaels, and

Gauls; the Sacites, or Scythians (the word comes from Assyrian captives,

Esak-ska and Saka, comparable to the Hebrew Isaac); the Goths, or Getai (the

root probably from the Biblical Gad, pronounced Gath); the Jutes of Jutland

(from the Tribe of Judah); and the Parsi (from Hebrew 'Paras,' which means

"the dispersed ones"), who settled Paris and whose name in Germanic

territory sound - shifted to Frisians.

References:

2. See John T. Waterman, A History of the German Language (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966), p. 28; Heinz F. Wendt, ed., Sprachen in Das Fisher Lexikon (Frankfurt am Main: Fisher, 1977), p. 101; and R. Priebsch and Collinson, The German Language (London: Faber, 1966), p. 69; see also pp. 58-70.

3. For a detailed description of the Germanic Sound Shift, see Waterman, A History, p. 24; Priebsch and Collinson, The German Language, pp. 58-70; or Wendt, Sprachen, p. 101.

4. See W. B. Lockwood, Indo European Philology (London: Hutchinson, 1969), p. 123.

5. For a summary of these theories, see Waterman, A History, pp. 28-29, and Priebsch and Collinson, The German Language, p. 68.

6. This article follows the professional linguistic convention of placing groups of related sounds in brackets.

7. See Waterman, A History, p. 28; Wendt, Sprachen, p. 101; and Priebsch and Collinson, The German Language, p. 69.

8. These sounds were not found in the original Indo-European language. They entered Germanic, Armenian, Greek, Celtic, Persian, and, to a lesser extent, several other languages during this same time period.

9. Even the same exception to the rules for gemination appeared in both languages. The r (and guttural fricatives) did not double in either Hebrew or in Germanic; instead, the vowel preceding the r lengthened, as in Hebrew berakh ('to bless') and Old English heran ('to hear').

10. See William Chomsky, Hebrew: The Eternal Language (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1957), pp. 55-56. William Gesenius makes frequent reference to remnants of other cases in Hebrew. See his works, Geschichte der hebraischen Sprache und Schrift (Hildesheim: Olms, 1973) and Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures, trans. Samuel Tregeles (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1979).

A Hebrew influence even explains what has been considered an exception to the rules for the Germanic Sound Shift. Whenever one of the six consonants appeared in the middle of a Germanic word, following a consonant, it did not shift. This follows the Hebrew rule, which states that the shift does not occur when the letter is immediately preceded by a consonant. For example, Hebrew harkanah and English harken both contain an unshifted k.

11. For details, see Blodgett, 'Phonological Similarities,' pp. 73-76.

12. See Lockwood, Indo European Philology, p. 123.

13. For details of the differences, see Blodgett, 'Phonological Similarities,' pp. 58-72.

14. See 'Hebrew Language' The Jewish Encyclopedia (New York: KTAV, 1964), 7:308; also Neh. 13:24.

15. See Alexis Muston, Israel of the Alps: A Complete History of the Waldenses and Their Colonies, 2 vols. (New York: AMS Press, 1978).

16. See 'Aramaic,' Encyclopedia Judaica, 16 vols. (Jerusalem: Keter, 1971), 3:262-66.

17. See Chomsky, Hebrew, pp. 92, 112. Aramaic also began shifting [d] to [z] rather than to [dh], but Chomsky doesn't mention this, perhaps because the Jews didn't adopt this aspect of the shift as consistently.

18. Izvestia o Chozarach i Russkich, as quoted and translated by Joseph C. Littke in Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, Jan. 1934, pp. 7-8.

22. Materialy dlia isoutchenia Evreiskago-Tatarskago yazyka (St. Petersburg: n.p., 1892), as quoted by Littke, in Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, p. 8. Chwolson, Pamiatniki drevnei pismennosti (St. Petersburg: n.p., 1892), as quoted by Littke, in Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, p. 9.

See Also:

Terry Blodgett: Hebrew Component

Hebrew Sources of Northern Tongues

Karl Rodosi, "Hebrew English Origins"